METHODS & TOOLS

SO THE FUTURE IS VERY DIFFERENT FROM TODAY - WHAT TO DO NEXT?

Whether we like to admit it or not, short-term thinking is entrenched in many of our political and economic systems – and as a result in many of our working assumptions. Many policy level decisions are taken with the next election in mind – usually a four or five year process, whilst quarterly reports dominate stock market sentiment and many business’ outlooks.

The focus on the short-term certainly has tactical benefits and for certain companies such as various value Fast Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG) retailers, short-term trends assume an understandable primacy. However, these short-term trends offer at best a glimpse, and at worst a misrepresentation of the deeper seated mega-trends that take longer to evolve but are more disruptive, and potentially a greater opportunity, to organisations.

Our current climate is characterised by incredible uncertainty; political, economic and social norms are being rewritten globally. This perhaps partially accounts for the ever-shortening business horizon detected in research since uncertainty breeds limited outlooks. Harvard Business Review notes that in its analysis of the ‘…extent to which the share prices of S&P 500 firms are driven by a firm’s present value of future growth options (PVGO) rather than cash flow from current operations[i].’

In the decade to 2015, firms’ degree of exploration decreased by 7% points—larger firms, including Apple and IBM, are even more affected with an average 10%-point reduction. The bottom line is that the focus on the short-term and on defending business models rather than exploring new ones represents a significant loss in future option value. Harvard Business Review (HBR) estimates that collectively, investors now value the future growth options of these firms relatively less, by $1Trillion[ii].’ This would seem proof enough that a myopic focus tends to generate less growth and value over the long term[iii].

A PATH FORWARDS

Organisations across a range of industries and a spectrum of sizes are being forced to adapt to ever changing consumers, rapidly evolving technology and a quickening of the business environment. Opportunities will increasingly need to be ‘discovered’ since technology alone does not constitute a strategy nor is it plug and play in the sense that a new tech overlay cannot compensate for a fundamental legacy infrastructure – whether mindset, technology or organisational structure.

Business would do well to begin a process of alignment, using deep-seated changes that fundamentally create change as a guide. Several of the key drivers of changes – known as megatrends (and including issues such as demographic change and the rise of emerging Asia) are forces larger and too complex than many standard industry-level trends normally interrogated by standard strategic tools such as Five Forces. However, taking the longer view can often feel irrelevant given that it can feels far away, and probably beyond the job tenure of most people who might perhaps consider it.

As most businesses are becoming aware – either through business model pressures, friction from grafting new technologies onto legacy systems or else organisational issues, a new level of planning is needed. A yearly competitive analysis of predefined competitors no longer suffices. New competitors, new pressures and new opportunities are emerging and cannot be ignored.

THE ROLE OF FUTURES THINKING

Futures thinking seeks to redress this dangerous imbalance, by providing a systemic framework for thinking about, imagining, and planning for the future. Futures thinking done well can help in:

-

Challenging our view of the world

-

Challenging our base assumptions

-

Preventing institutional blindness

-

Constantly assessing the wider context in which businesses operate

-

Prevent rigidity throughout the organisation

-

Developing organisational agility

Ultimately these benefits can help safeguard a business: futurism isn’t an exact science but it’s better to be roughly write than precisely wrong. Several companies, including Unilever, ‘…have stopped producing detailed quarterly reports in an effort to focus on making investment decisions that stretch the company’s horizons. For Unilever it means that short-term forward-planning is replaced with a robust purpose – a ‘Sustainable Living Plan’ to double the size of the business and lower its environmental impact[iv].’

The goal of futures thinking is not to predict the future per se. Nor should it be solely technologically oriented since the rise of Airbnb or Uber could not have been reasonably foreseen through smartphone technology and WiFi alone[v]. At its core, futures thinking lends us a sort of mental flexibility, as well as the ability to think through trends and possibilities that are outside mainstream thought and hence easily dismissed. This allows stakeholders to have structured conversations about uncertainty. It could also be argued that futures thinking is no longer the preserve of futurists – the skills and toolset can be acquired, used, and arguably should be used, by and person charged with long range decision and strategy making[vi]. That said, numerous companies such as Disney, Ford P&G, and Intel, have begun the process of mainstreaming corporate futurists[vii].

A GUIDE TO THE TOOLS AND PROCESSES

We aim to provide a practical guide to using futures thinking, bringing together the best ideas and suggestions for ways to approach futures thinking, including methodologies and case studies highlighting successful and less successful attempts at futuring. There are over 25 techniques that could be considered part of futures analysis, ranging from workshops to long term processes[viii].

[i] https://hbr.org/2015/11/dont-let-your-company-get-trapped-by-success

[ii] https://hbr.org/2015/11/dont-let-your-company-get-trapped-by-success

[iii] https://hbr.org/2017/02/an-agenda-for-the-future-of-global-business

AMONGST THE SERVICES WE OFFER:

Scenario Planning

SWOT

Horizon Scanning

3 Horizon

DELPHI Method

Futures Wheel

Cross Impact Analysis

NEXT

ENTREPRENEUR, LEADER, MANAGER

CEOforesight

turning point

E C O N O M I C S

SCENARIO PLANNING

German Field Marshal von Moltke, is widely credited with pioneering a new approach to directing armies in the field that entailed the creation of a series of options rather than prescribing a single plan[i]. This view was later referenced in public by both Winston Churchill and Dwight D. Eisenhower who noted the lack of value in plans but the richness of planning itself. The increase in uncertainty – whether economic or geopolitical, combined with the accelerating speed of many markets has further impacted this assessment. Far from current events rendering scenarios impractical, they provide a real reason for embracing them at a strategic level – by accepting that more than one future is possible and that a definite future cannot be ascertained.

What are scenarios for?

WHAT ARE SCENARIOS FOR?

Scenarios represent a process to structure, think about, and plan for, key future uncertainties. The aim is to improve strategic planning processes and outcomes. Typically, four scenarios are crafted – none of which are meant to predict the future but rather provide the means to consider key drivers and impacts cognizant of possible future developments[ii].

Many organisations try to leap from horizon scanning to strategizing and setting priorities, without a period of reflection, sense-making and understanding. A number of foresight tools can help in this period, perhaps most notably scenarios.

Scenarios form a key part of an executives’ toolkit, enabling them to embrace uncertainty rather than attempt to ‘…predict discrete events - as they develop strategies that can withstand the profound macro changes transforming the global external environment[iii].’

What commitments are needed?

WHAT COMMITMENTS ARE NEEDED?

Although rough and ready scenarios can be crafted in little time, a thorough scenario planning exercise represents a significant commitment to foresight more generally – and this unsurprisingly requires time. The process can be resource hungry in its demand on key stakeholders’ time and mental focus; in fact it is perhaps one of the more involved futures processes when applied appropriately. Given the breadth of input and consultation needed and the realities of limited free time amongst executives, the process could even last months, with several workshops taking place.

The process

THE PROCESS

Such senior management/executive workshops should ideally take place under the guidance of an expert facilitator – not just to ensure correct processes but to also enable an impartial atmosphere not hostage to managerial status or politics. In effect these are facilitated brainstorming sessions, out of which a set of scenarios running the gamut from probable to implausible are produced. More importantly, debate then starts as to the resultant impact on the business in terms of both opportunities and challenges.

Figure 1: The steps of scenario planning adapted from Firms Consulting[i]

From inception of the process through the construction of the scenarios, it is critical to conduct research and feed it in to the process. This is especially true at the beginning of the process to both inform and guide the process and inform key stakeholders. Desk-based research should be used to initiate, provoke discussion and, later, fill in gaps evident within the scenarios themselves but other methodologies such as the Delphi technique could be used to help identify pertinent issues.

There are a number of tools available to facilitate the research phase, one of the more well-known is in conducting a Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Legal and Environmental (PESTLE) analysis to help stakeholders to identify the range of drivers in a given situation. This approach has several variants – STEEP, PEST and SEPTED (socio-cultural, economy, politics, technology, ecology, demographics) but the framework they use is similar – as are the issues they identify. A basic simplified and generalized PESTLE analysis could be distilled as such;

Figure 2: A simplified and incomplete example of PESTLE groupings

Deciding on axis for the scenarios (assuming a standard 2x2 grid) is perhaps the most important part of the actual process since it shapes outcomes thereafter. It involves choosing the two key uncertainties (sometimes at megatrend level) and inserting them into two orthogonal axes. From this a matrix is created allowing the creation of four unique yet plausible quadrants –each allowing a different future to be explored.

Drivers should then be sorted into two groups; one representing certain changes and the other uncertain. Within each group, the potential impact of each driver can be assessed and roughly ranked. Sometimes known changes may well form a key role of the scenario raison d’etre - such as ageing – but many successful scenarios examine two (or more) of the prime uncertainties.

Once the axes are agreed upon, most practitioners advocate testing a set of key questions in each box, or quadrant. Customer-centric approaches could include asking ‘What happens to our customers in this scenario?’ ‘how does our value proposition change in light of this development?” or ‘Who wins and who loses in this scenario?’ Such questions can stimulate and inform scenario narrative and development. It is also important, in order to gain traction, that the scenarios have pithy, or catchy, names.

A real life example of a completed matrix, constructed by Members of the Vision of Pediatrics 2020 Task Force looking to assess how two fairly narrow industry uncertainties could impact the role of the pediatrician, is provided below in figure 3.

However, the scenario planning process is not an end in and of itself. The scenario process –although mentally useful – will not succeed without the scenarios being circulated extensively - whether as information, a strategic tool or as a communication aid. If the scenarios are not used to help strengthen business decisions in the here and now, they are not being used optimally.

WHAT ARE THE BENEFITS?

Scenario planning is gaining traction amongst futures practitioners over other methods such as forecasting and modelling as the tool is more timely and flexible (and in this sense relevant[i]) especially given the uncertainty in which the world now finds itself. A 2013 survey[ii] of 77 large European companies found that formal ‘strategic foresight’ efforts (of which scenario planning was a significant part) deliver value via four platforms:

-

Enhancing capacity to perceive change

-

Improving capacity to interpret and respond to change

-

Providing a degree of influence on other actors, and

-

Enhancing capacity for organisational learning.

Perhaps the most important facet of these platforms of value is the development of an awareness of how practitioners think – including their biases and in-built assumptions. Indeed, value is found in not just how the scenarios are ‘..embedded in – but also provide vital links between organisational processes such as strategy making, innovation, risk management, public affairs, and leadership development.’ Since scenarios generally represent unthreatening scenarios and provide freedom of thought beyond normal boundaries, they enable practitioners to examine both inconceivable and otherwise imperceptible changes[iii].

IN PRACTICE

Embedding scenario planning within an organisations’ DNA and subsequently its’ management process, can confer significant competitive advantage. IBM, for example, has been using futures methods including scenarios to inform its annual Global Technology Outlook report for over three decades. The process of engaging and updating this process yearly has positioned IBM as a thought-leader within the technological foresight space and, as the company states, enables ‘…sound decisions and investments in future technology directions[i].’

In addition to strategically planning for future possibilities, scenario planning can benefit in the short-term if applied appropriately. In 2008, prior to the collapse of Lehman Brothers, bond giant Pimco conducted a scenario planning exercise to map out and better understand the potential ways that the then impending crisis could unfold. Of the scenarios created, Pimco placed only a <5 percent chance on the ‘disorderly failure,’ scenario but nevertheless crafted detailed contingency plans for all outcomes, including this one. Following Lehman’s collapse, Pimco was able to rapidly dump their bonds at short notice and gain a competitive advantage over those still struggling to comprehend what had happened. Then-Pimco CEO Mohamed el-Erian duly notes that ‘…it’s a lot less expensive to prepare plans for events that never happen than to have no plans for events that do happen[ii].’

There are countless examples of strategic decisions being taken as a result of the scenario planning process. In 2001, UPS’ acquisition of Mail Boxes Etc. gave UPS more than 3,500 retail store locations in the U.S. in addition to its existing network of large hubs used as mail-sorting facilities. Of four scenarios crafted, one was a huge influence on the decision to go ahead with the acquisition. The scenario in question, dubbed ‘Brave New World’ described a deregulated, globalised marketplace, which at the time represented a significant departure from their operating environment. MIT Sloan notes that ‘…it was this scenario that convinced management to invest in retail locations[iii].’

The efficacy of successful scenario planning is such that Kinaxis and Deloitte Consulting have announced an alliance to develop scenario planning capabilities for business supply chains. The ‘what if’ scenarios are intended for existing customers, aiming to provide value and develop clients’ capabilities in meeting rapidly reconfiguring demand and situations in real-time[iv].

As IBM, Pimco and UPS demonstrate, the use of multiple scenarios can incentivize executives into more agile and flexible strategies. Since executives tend to decide on strategies optimized for a given environment, it is important not to discard past scenarios given the certainty that the current environment will change. In this sense, the very act of scenario construction can emphasise the importance of flexibility for executives – whether it be in asset terms, or in business approaches[v].

[iii] http://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/how-scenario-planning-influences-strategic-decisions/

[iv] https://www.enterprisetimes.co.uk/2016/05/04/scenario-planning-back-vogue/

[v] http://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/how-scenario-planning-influences-strategic-decisions/

WHAT TO AVOID

It cannot be emphasized that the scenario planning process alone does not confer its’ benefits automatically; the outcomes must be practiced, prepared for and form part of ongoing strategy. That said, scenario planning does not refer to a singular set of practices. The type pioneered by Pierre Wack at Shell in the 70’s was typically data heavy and attempted to predict the future with precision. Whilst generally this method of scenario planning has subsided in popularity, owing to its expense and the excessive time needed[i].

Some of the advantages of scenario planning can also become weaknesses in the right circumstances. Whilst, for example, thy are a good method for disrupting groupthink, they themselves can create groupthink – especially if the organisation begins to think in terms of four possible outcomes (or in badly constructed scenarios, even fewer)[ii]. There is also the possibility that at least two scenarios in any 2x2 grid are hamstriung from the get-go – very little is learnt from excessively optimistic scenarios whilst the inevitable challenging scenario can be dismissed by people afraid of the consequences. It is important though to include such a scenario in most circumstances. In 2001, one investment bank for instance imagined a worst case scenario to equate to a 5 percent revenue decline. This was far too optimistic given the downturn that was to occur. McKinsey further notes that in scenario construction ‘…it is easy to be trapped by the past. We are typically too optimistic going into a downturn and too pessimistic on the way out[iii].’

Take for example, German energy companies in 2011. Most relied on classic scenarios – consisting of a base case with more optimistic and negative variants on either side. The Japanese nuclear disaster at Fukushima rewrote the base case overnight – vastly accelerating the switch to renewables and putting the price of power 50 percent beyond the gloomiest predictions on offer. As a result many power producers had to write off tens of billions of euros[iv].

Scenario planning interventions are not always successful, even when they are used correctly. Through their scenario process it became apparent to the senior management and board at Beta Co. that their then current products would eventually become obsolete by disruptive technologies. Nevertheless, a low risk appetite and inert organisational culture created a response of doubling-down on their existing areas of expertise. Beta Co. managers even considered diversifying their product line during scenario planning, but instead followed a risk averse path to continue with their main product line where they were experienced. Clearly, a successful change management process and an agile business culture that accepts and encourages some risk are both prerequisites for successful scenario planning where disruption is likely[v]. This point cannot be overstated in its importance as a barrier for the successful use of scenario planning.

[i] http://www.eco-business.com/news/scenario-planning-for-turbulent-world/

[ii] https://hbr.org/2013/05/living-in-the-futures

[iii] https://hbr.org/2013/05/living-in-the-futures

[i] https://hbr.org/2016/06/strategic-plans-are-less-important-than-strategic-planning

HORIZON SCANNING

The burgeoning 2008 credit crisis that would become the global financial crisis accounted for many corporate victims. In these extreme circumstances, Countrywide Financial Corporation – like many of its peers – never saw its collapse coming. Indeed. In the middle of the crisis, now former CEO Angelo Mozilo noted that ‘…everyone looks to history to interpret the present and predict the future. This is unlike anything I thought even three months ago[i].’ Whilst Mr Mozilo is in ‘good’ company with the CEO’s of former companies, such as Blockbuster or Blackberry who likewise failed to see change coming, his argument that history will help predict the future was demonstrably wrong. Pimco, for one, had contingencies for such an eventually as the Lehman Brothers collapse.

WHAT IS HORIZON SCANNING FOR?

Horizon scanning is a technique that works much like an early-warning radar; detecting early signals of potentially important change. Horizon scanning for future risks is limited, both in form and function, at many organisations. PwC notes that only 12 percent of organisations use any form of stress testing to test risk assumptions and plans[ii]. A higher percentage, no doubt, employ more simplified versions of horizon scanning but not all are able to tie concrete business results to their horizon scanning activities.

The OECD notes that the ‘…method calls for determining what is constant, what changes, and what constantly changes[iii].’ Such a method is central to effective horizon scanning, which should be able to distinguish between noise and real signals. Indeed, perhaps the core of horizon scanning is to assess what is truly new, important and underappreciated – such signals are usually found on the periphery on current assumptions but not always.

A robust and well executed horizon scanning exercise will challenge our existing assumptions surrounding continuity and change, and explore how issues at the edge could impact us in the medium to long term.

WHAT COMMITMENTS ARE NEEDED?

The act of horizon scanning itself is generally a low resource activity. Horizon scanning is usually centred on desk research, either by individuals or small groups of people – whether trained futurists or experts in a given knowledge area. Desk research should ideally synthesize a variety of sources from government reports, NGO sources, international organisations and companies to research communities (including higher education).

The output should then help inform the broader picture, and this stage of the process does require a degree of management and executive buy-in not needed to initiate a horizon scanning process. This it is important for executives and senior management to become participating consumers of horizon level trends and to develop a sense of judgement over individual scans’ efficacy[iv].

More recently, automated horizon scanning services have appeared[v]. SRI International’s offering, for example, ‘…trawls the academic literature (within healthcare) from over 17 million academics and uses things like trajectory mapping to underpin its AI engine and provide users with what it believes are the hot trends in any given field.’ Such services will increasingly work alongside, and in some cases replace, the human element.

[ii] http://www.pwc.co.uk/services/audit-assurance/operational-resilience-benchmark-tool.html

[v] https://dzone.com/articles/researchers-hope-to-automate-horizon-scanning

THE PROCESS

As the SRI example shows, an emerging range of techniques and technologies can be employed in the service of horizon scanning. AT Kearney notes that ‘..a variety of companies, including Palantir and Recorded Future, offer big data analytics to enhance the trend analysis and weak signal identification stages of horizon scanning[i].’ For dedicated desk research analysts, it is important that horizon scanners constantly look to expand their own horizons beyond the usual information and intelligence sources. This could involve the consultation of external experts for example.

WHAT ARE THE BENEFITS?

Perhaps the key attraction of horizon scanning as a stand-alone activity, whether done as desk research analysis or as an automated software process is its low resource intensity.

It can also complement a more holistic futures-thinking outlook; for example by feeding content for a Delphi survey, scenario thinking or informing a Three Horizons process. It should be noted that in contrast to many futures techniques, horizon scanning can happen without overt outside assistance.

The level at which horizon scanning can prove beneficial is also of import; anybody with a degree of strategic interest in their job – from finance to HR and marketing to IT can benefit enormously from developing horizon scanning capacities – whether formally or informally.

IN PRACTICE

The use of horizon scanning is a reasonably well established practice within many organisations, particularly larger ones across both the private and public sectors. Ericsson, for example, uses scanning for identifying new technologies, while international law firm Eversheds uses the tool to gain insights into retail finance[i].

There are also examples of horizon scanning leading to clear competitive advantage. MGA Entertainment, maker of the dolls line ‘Bratz,’ had recognised around the millennium that preteen girls were changing – both maturing quicker and developing a more sophisticated taste in dolls. As a result of these shifts, rivals Mattel (the makers of Barbie) lost 20 percent of its market share between 2001 and 2004 and had its target market narrowed from girls aged three through eleven to girls aged three to five. MGA effectively used horizon scanning to craft a new market niche and catch its main competitor unaware[ii].

Anheuser-Busch also used horizon scanning before launching its low-carb category, in 2002. By March 2004 it had captured 5.7 percent of the light beer category in the U.S, whilst market followers such as Coors peaked at 0.4 percent of market share. Anheuser-Busch company research in the 1980s had shown that consumers would be interested in a ‘healthier’ beer. Acting on this research had proved illusory until the low carb trend emerged in the wider food and beverage market. The emergence of this trend, coupled with groundwork done over the years, gave Anheuser-Busch a start in a new niche at a time when others were busy with other beer branding exercises[iii].

WHAT TO AVOID

A report to the UK select committee prepared by Jon Day the chairman of the Joint Intelligence Committee titled Review of Cross-Government Horizon Scanning believes that, ‘…horizon scanning products are often lengthy, and poorly presented, making them harder to digest and easier to ignore. It is also rare for them to include…an analysis of how the information presented could be used to inform decision making[iv].’ These issues largely relate to how the methods are (or have been) pursued, rather than the method itself. There are however, a number of issues with horizon scanning.

It is;

-

An ongoing process that requires active management.

-

Unable to be fully outsourced (although automation might change this)

-

Not necessarily embedded in wider change programme or management.

-

Quality will depend on the analysts’ resources and breadth of knowledge.

[i] https://www.atkearney.com/gbpc/thought-leadership/detail/-/asset_publisher/03JmqNRaRZj7/content/no-one-saw-it-coming/10192?inheritRedirect=false&redirect=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.atkearney.com%2Fgbpc%2Fthought-leadership%2Fdetail%3Fp_p_id%3D101_INSTANCE_03JmqNRaRZj7%26p_p_lifecycle%3D0%26p_p_state%3Dnormal%26p_p_mode%3Dview%26p_p_col_id%3Dcolumn-2%26p_p_col_pos%3D1%26p_p_col_count%3D2

[ii] https://hbr.org/2005/11/scanning-the-periphery?webSyncID=39938744-e905-949b-a952-32a1edc72745&sessionGUID=146eb9de-6632-0e4e-c4ed-124102b66e41

[iii] https://hbr.org/2005/11/scanning-the-periphery?webSyncID=39938744-e905-949b-a952-32a1edc72745&sessionGUID=146eb9de-6632-0e4e-c4ed-124102b66e41

[iv] http://www.futurejustice.org/blog/blog/horizon-scanning/

3 HORIZON

Change is a given, and the rate of corporate churn is rising. 80 percent of the companies that existed before 1980 are no longer around, and of the remainder, an estimated 17 percent could cease operations by 2021[i]. The likelihood of corporate survival are lessening – in 1970 companies listed had a high chance of surviving the following five years (92 percent), whereas companies listing between 2000 and 2009 had only a 63 percent chance of five-year survival, even allowing for the dot com bust and global financial crisis. This decline has many factors, but an imbalance between the priority given the short, medium and long term is clearly demonstrable in many famous corporate demises.

As organisations mature, they typically encounter decline in growth as their core competency becomes a source of inertia. Consistent growth requires effective balancing of the urgent, the future and the somewhat awkward space in between.

What is Three Horizons for?

Three Horizons is a graphical approach that demonstrates how the relative importance of issues will change over time. In this sense, it shows the ‘bigger picture,’ – that the urgent issues occupying much of an executives’ time may in fact be far less important than some of the longer term issues they are happy to ignore or postpone. There are numerous examples of the more important issues being relegated in favour of more urgent issues; at the political level at least, climate change remains a prime example.

Three Horizons (3H) thus helps participants (usually groups) work through complex issues and uncertainty. Concurrently the approach helps generate agency ‘…in ways not always addressed by existing futures approaches[ii].’

WHAT COMMITMENTS ARE NEEDED?

The creation of a 3H framework is a relatively time-light, resource light activity in and of itself although horizon scanning is usually required to inform the creation of 3H. To create one, an organisation merely needs to plot the results of their horizon scanning according to time (x-axis) and importance/impact (y-axis) as defined by the appropriate metric. The y-axis can also represent the degree of strategic fit with the external environment. The real commitment lies in the application of the framework after it has been created; i.e. in insuring the framework informs strategy and practice.

THE PROCESS

The framework typically looks something like the figure below, taken from Andrew Curry and Anthony Hodgson[iii].

Figure 5: A 3H framework

[i] https://hbr.org/2016/12/the-scary-truth-about-corporate-survival

It should be noted that although the x-axis, denotes time, it does not suggest that the technologies or trends under each horizon should be dealt with sequentially. Rather, all should be given attention concurrently – but the strategies and plans will vary according to horizon. The x-axis denotes the process over time in which such drivers, issues or ventures will move across the horizons.

Horizon One (H1):

-

Indicates the company’s core businesses today

-

Denotes areas of highest activity.

-

This first horizon involves implementing innovations that improve your current operations and efficiencies[i].

Horizon Two (H2):

-

Includes ideas, trends and technologies that will become central to the core of the company in the coming years – either as central propositions or as replacements for current models.

-

Includes extensions but also new directions that may require new competencies, ways of thinking and require time to build.

-

Regardless of their form, many inputs in H2 will have the potential to shift the company’s revenue base, business model and organisational model.

Horizon Three (H3):

-

Includes weak signals and emerging issues that could form future growth poles.

-

These innovations are often highly disruptive to current business model and organisational structures.

-

Contains a wide range of unknowable impacts that demand further futures investigations- perhaps through futures wheels, horizon scanning or even scenario planning.

WHAT ARE THE BENEFITS?

The primary benefit of the 3H framework is to give a structure for companies to assess future directions, shifts and growth opportunities without sacrificing the array of urgent needs that confront any business in the present.

It is easy, given the demands placed on companies, whether through changing consumer behavior, legacy technology or thinking, outmoded organisational models or unclear leadership, to focus on the immediate short term necessities. These can overwhelm to the point of neglecting more important longer term issues. Business leaders and executives use the 3H model as a way of ‘…balancing attention to and investments in both current performance and opportunities for growth[ii]..

IN PRACTICE

Merck have adopted and adapted a 3H model to help drive IT[iii]. Merck notes that ‘…it’s important to make sure the organization is structured in a way to drive near-term results while ensuring that longer-term results can also be achieved.’ In the first horizon, Merck’s goal is to provide better service, consolidate tech and reduce costs. Innovation is not absent in this horizon but is geared towards cost reduction (for example, automation).

Merck’s second horizon is on an 18 to 30 month timeline (others are longer than this) and Merck’s IT department stresses that this ‘…horizon requires us to work closely with our business colleagues because it’s not something IT can do alone.’

Horizon three features longer term issues – Merck notes that 3D printing offers some interesting impacts on the way Merck develops drugs and perform trials.

3H has been used to facilitate change and innovation. A major European oil and gas company, seeking to chart a transition to renewable energy used 3H to develop a credible research and development story to guide resource deployment[iv]. In 2007, the Carnegie UK Trust together with partners used 3H to integrate material from an internal inquiry and develop a future oriented scenario. This supported strategic visioning and helped determining key transformative (H2) actions.

WHAT TO AVOID

When some of the greatest tech companies of yesteryear are considered, a surprising incidence is visible in all of Kodak, Sun, AT&T, Xerox, Silicon Graphics and more[v]. Not one abandoned their long-term R&D strategies – indeed Kodak even developed the digital camera. In fact, all had invested heavily in the long-term; which is widely seen as a route for success being ignored all too often on today’s world. The problem all of these companies had – and a continuing but largely underappreciated issue with today’s companies – is that none could bring their long-term investments to fruition. Whether through flawed management or organisational design, none were able to successfully transition their ideas and plans from H3 through H2 and into H1.

Perhaps the biggest hurdle, both mental and organisational lies with Horizon 2. Understandably, Horizon 1 attracts the majority of time, talent and managerial attention yet this leads to problems. Harvard Business Review notes that in its analysis of the ‘…extent to which the share prices of S&P 500 firms are driven by a firm’s present value of future growth options (PVGO) rather than cash flow from current operations[vi].’ In the decade to 2015, firms’ degree of exploration decreased by 7% points—larger firms, including Apple and IBM, are even more affected with an average 10%-point reduction. The bottom line is that the focus on the short-term and on defending business models rather than exploring new ones represents a significant loss in future option value. HBR estimates that collectively, investors now value the future growth options of these firms relatively less, by $1Trillion[vii].’ Business is not unaware of this issue; hence Horizon 3 also attracts some attention; most managers are at least partially appreciative of long-term investments and plans. Horizon 2 however can be a kind of no-mans-land. Projects in Horizon 2 argues Harvard Business Review, invariably require ‘…customized processes, metrics and performance targets.’

It may also require organisational dexterity. When Cisco CEO John Chambers saw that growth opportunities were in developing economies, he also noted that these areas would not receive the attention they needed given their existing standard geographic sales coverage. Instead, Cisco crafted a single territory concept headed by a single sales exec. This executive segregated a dozen or so emerging markets for Horizon 2 in which they focus on transformational deals and left the rest of Horizon 3. Horizon 2 countries required a degree of executive action and attention that was unable to be provided when all markets were though of under a traditional mindset.

The rise of the platform economy and subsequent platformization of many business models stands as a case in point for the perils of ignoring H2. Thirteen of the tope thirty global brands are now platform companies – each with the ability to scale quickly thanks to the minimal (or nonexistent) marginal costs of production[viii]. Although Amazon et al appeared before 2000, it was in 2010 when the power of platforms began to show. In that year, Ainbnb went from about 100,000 nights booked in January, to 800,000 nights booked by the end of the year[ix]. 2010 also saw Amazon post 40 percent revenue growth – its highest since 2000 – with net sales increasing by over 39 percent to around $34 billion[x]. It was clear at this point that platforms had moved way beyond music and other early pioneers; it was time to place platforms in Horizon 2 as something that could potentially shift business lines within three years or so. Across many industries, few incumbents did so.

The explosion of FinTech in the past 24 months stands as testament. By 2020, different business models could impact 80 percent of existing banking revenues[xi]. There is a real risk for banks of being pecked to death by the very platforms they eschewed for years. 52 percent of banking execs now expect to work with new digital partners within two years, but the risk of banks simply providing the plumbing for the wider banking ecosystem is now very real. Many are trying to co-opt platform elements onto a fundamentally legacy model; a position that is likely to be usurped by new platform players such as Atom Bank in the UK.

Other industries have been caught flat footed by issues they probably considered too distant or irrelevant for their particular industry segment. 80 percent of insurance CEOs are concerned about the relevance of their products and services for example[xii], with new models and methods such as P2P insurance holding the potential to restructure the entire market. However, studies show insurers overly concerned with H1 issues, with one study noting that incumbents are largely ‘…'too busy to innovate' lacking time, resources and the right culture[xiii].’ The danger is that what may be difficult but manageable as an H2 issues becomes too large to deal with effectively as an H1 issue. Only 17 percent on insurers intend to invest significantly in business model transformation in the period to 2019[xiv] even though close to half on insurers’ business models are already being disrupted by new competitors[xv] who are using platforms to prioritise customer experience[xvi]. The dangers of an H2 blindspot are abundantly clear.

Industries untouched by the wider digital revolution are perhaps most at risk from the confluence of the platform economy and this blindspot (or perhaps, any sort of foresight methodology). In real estate, technology is already shifting the role of real estate agents from an information arbiter towards being a local market expert and service provider. Real is an app and network built as a platform for agents, allowing them to circumvent the conventional brokerage model[xvii], for example. Unlike the platform giants of the ecommerce, the risk for incumbents in real estate and numerous industries beyond is the disaggregation of their business processes and model into undreds of little parts that are then not only done more efficiently by others but with a better slant towards customer needs and experience.

[i] https://paul4innovating.com/2010/09/10/the-three-horizon-approach-to-innovation/

[ii] http://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/enduring-ideas-the-three-horizons-of-growth

[iii] https://www.accenture.com/us-en/insight-perspectives-life-sciences-merck-innovative-horizons

[iv] http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-08388-210247

[v] https://hbr.org/2007/07/to-succeed-in-the-long-term-focus-on-the-middle-term

[vi] https://hbr.org/2015/11/dont-let-your-company-get-trapped-by-success

[vii] https://hbr.org/2015/11/dont-let-your-company-get-trapped-by-success

[viii] http://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/platform-strategy-and-the-internet-of-things/

[ix] https://techcrunch.com/2011/01/06/airbnb-2010/

[x] https://www.digitalcommerce360.com/2011/01/27/amazon-sales-and-profits-boom-2010/

[xi] https://www.accenture.com/us-en/digital-transformation-banking

[xii] https://home.kpmg.com/xx/en/home/insights/2016/11/embracing-disruption-a-fundamental-rethink-of-the-business.html

[xiii] http://www.strategic-risk-global.com/insurance-industry-too-busy-to-innovate/1418156.article

[xiv] https://home.kpmg.com/xx/en/home/insights/2016/10/transforming-for-the-future-insurance-ceos.html

[xv] https://home.kpmg.com/xx/en/home/insights/2016/03/insurers-face-insurance-innovation-fs.html

[xvi] http://www.theactuary.com/news/2016/07/insurtech-startups-and-insurers-can-prosper-by-working-together-says-pwc/

[xvii] http://www.curbed.com/2016/3/14/11224322/home-real-estate-app-agent-broker

DELPHI METHOD

RAND is credited with the development of the Delphi Method in the 1950s, with the original aim of forecasting the impact of technology on warfare. It’s rationale is based on a scaled version of the truism that two heads are better than one, in which a group of experts reply to questionnaires and subsequently receive feedback in the form of a statistical breakdown of the group response/average. Iteration is key – after this, the process repeats itself to reduce the range of possible responses and helping build consensus. As RAND notes, the ‘…Delphi Method has been widely adopted and is still in use today[i].’

WHAT IS DELPHI FOR?

Delphi is a qualitative process, as are many futures methods, that runs as a consultation process involving a wide group of participants. The questions are predefined and seek participant opinion on when events are most likely to happen as well as what their underlying influences are.

Delphi’s distinguishing feature that contrasts it to other data gathering and analytical techniques lies in the multiple iterations that aim to smooth out outlier opinions and build consensus. This feedback process enables participants to reassess their initial judgements based on comments and feedback from other panelists.

One increasingly popular process is to combine Delphi techniques with scenario planning by using the output of the former to act as input for the information intensive latter. Delphi outcomes can not only enrich the scenario story but also simplify what can be a complicated process. Furthermore, some of the more extreme ideas discarded in the earlier iterations of the Delphi process could form interesting extreme scenarios or wildcards.

What commitments are needed?

The process of conducting a Delphi study is time-intensive, with practitioners suggesting that a minimum of 45 days for the administration of a Delphi study is necessary[ii]. It has also been suggested that a two-week time period is allowed between iterations or rounds, although evidence exists of shortened practices.

Another commitment, which can both extend the timeline of the process is the sourcing of around 20 or so knowledgeable panellist.

THE PROCESS

The creation of an aligned set of questions is the first step along with the appointment of a moderator to administer the steps in the consultation that follow. The moderator guides the process but, it should be noted, not participant responses. Next a panel of experts, perhaps broad, but all with direct experience and expertise in the subject area should be chosen and enlisted and when complete, the question set circulated.

An abridged set of questions, taken from a study aiming to refine national asthma indicators in Australia, is shown below.

[i] http://www.rand.org/topics/delphi-method.html

[ii] http://pareonline.net/pdf/v12n10.pdf

Figure 6: Abridged Delphi survey on the priorities for national indicators for asthma data indicators in Australia[i]

[i] http://www.aihw.gov.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=6442453831

The Delphi approach blends individual decision making with social learning that evolves throughout the iterative process (featuring a number of rounds), summarised in the figure below and then explained in more depth.

Figure 7: Simplified Delphi process[i]

[i] http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S0103-21002012000600026&script=sci_arttext&tlng=en

Round 1: Individuals offer first-round estimates (or votes) of either an open questionnaire, or less commonly a closed questionnaire, in complete anonymity. Anonymity insulates group members from reputational pressures and thus reduces the problem of self-silencing. After receiving subjects’ responses, the moderator should convert the collected information into a well-structured questionnaire if not already done so.

Round 2: Next, a cycle of re-estimations (or repeated voting) occurs, with a usual requirement that second-round estimates have to fall within the middle quartiles (25 to 75 percent) of the first round[i]. Consensus generally begins – at least tentatively -in this round.

Round 3: This process is repeated, often featuring pauses for group discussion, until the panellists converge on a given estimate. Harvard Business Review notes that ‘…a simple (and more easily administered) alternative is a system in which ultimate judgments or votes are given anonymously but only after deliberation[ii].’ However, using a conventional process and especially when compared to the previous round, only a slight increase in the degree of consensus should be expected.

Round 4: The fourth round is often the final round, although the number of iterations depends largely on the degree of consensus sought by the moderator; it can vary from three to five or more. If needed, this process can be extended by a couple of rounds to ensure consensus and to explain decision making. In this round, the list of remaining items, their ratings, minority opinions, and items achieving consensus are distributed to the panellists, offering them a final opportunity to revise their judgments.

WHAT ARE THE BENEFITS?

There are several advantages to using the Delphi Method – perhaps the most notable is its inherent versatility. A range of other advantages exist:

-

Anonymity of responses negates domination by a single personality.

-

Can be conducted remotely, allowing participation from a global panel.

-

Panelists have time to carefully consider opinions and points of view.

-

Delphi clearly highlights the degree to which there is consensus.

-

Develops a risk radar for a given topic.

-

For participants, there are two main advantages. One, there is a psychological effect (in gathering further information between rounds) and two, a communication effect in being forced to express ideas in a clear and concise way.

-

The outcomes allow for analyses, rankings and priority-settings at a strategic and managerial level.

-

The output is in a form which is operational – even for those without much futures expertise or experience.

-

Delphi is action oriented, which appeals to many unused to futures, yet the process allows for and perhaps even compels longer-term thinking.

Although useful, Delphi results alone are not a guarantee of good decision making. Their efficacy is enhanced however, when they are shaped into or help inform a range of scenarios. Harvard Business Review cites an example of a panel’s prediction of rising Alzheimer’s diagnosis by, say, 2025. This alone is of limited value to a health care company, but exploring who might be impacted – from patients to families and health systems – and the relevant long term consequences could provide real strategic insight[iii].

IN PRACTICE

The Delphi method is used primarily when a long-term issue (or perhaps series of issues) require assessment. For example, in the 1990s, a major US television network enacted a Delphi process to look at the rise of HDTV, which it correctly concluded would take longer than was conventionally held. As a result, the network avoided heavy investment in needing to switch its equipment and was able to better plan for the digital switch[iv].

Delphi can also be used to formulate guidelines and plans; for example Delphi was used in the development of national clinical guidelines for prescription of lower-limb prostheses in the US[v].

Delphi is also scalable. Along with its partners, PwC sought to ask the question ‘…what future awaits the energy system in Germany, Europe and the world in the year 2040 and beyond?’ In 2014, PwC started interviews with 80 distinguished experts in order to form prospective questions. These theses were then submitted to a panel of more than 350 international experts, who evaluated 56 posited theses in a written survey, rating each thesis in terms of its overall likelihood, timescale and regional impact. The output forms a considerable piece of research and platform for further thought leadership. For example, one thesis deemed likely or certain by 63 percent of panelists suggested that ‘…by 2040 developing countries and emerging economies will have abandoned subsidies for fossil energy sources and nuclear power in view of the significant strain on national budgets[vi].’

Delphi projects also work as a prelude to strategy. Sloan MIT covers the story of a web-based project undertaken with a panel of hackers, to ascertain certain steps they would take in initiating a cyberattack. The ultimate goal was to define what an adaptive cybersecurity strategy should look like given the probably path taken by hackers[vii].

WHAT TO AVOID

It is accepted that there have been many poorly conducted Delphi projects, but this does not equate with the process itself being inadequate. The technique and its application should not be conflated, as it often appears to be. Poorly designed Delphi studies will inevitably lead to poor quality data and poor outcomes. It should be noted however that Delphi, although flexible, is not well suited to all avenues of enquiry. Complex issues that cannot be reduced or in the case of a need for alternatives are generally better suited when combined with other futures techniques, such as scenario planning[viii].

That said, the method does have a number of inherent disadvantages, such as:

-

Results are dependent on the quality of the participants

-

The top experts may be difficult to recruit, whilst expertise can be narrow and thus inappropriate for what is still a futures thinking exercise.

-

Experts are not necessarily futurists – leading to future events to be judged in isolation. Cross-impact analysis (or perhaps even scenario thinking) could be inserted here.

-

Delphi studies are fairly time-consuming, labour intensive and require (external) expert preparation. Costs can be an issue.

-

The consensus obtained in the second round can often prove artificial.

-

Results do not make facts but this point is often forgotten.

-

‘It is often difficult to convince people to answer a questionnaire twice or more and incentives may be needed (e.g. that the experts receive the results). The dropout-rate increases after the second or third round, so most current studies are limited to preparation and two rounds[ix].’

[i] https://hbr.org/2014/12/making-dumb-groups-smarter

[ii] https://hbr.org/2014/12/making-dumb-groups-smarter

[iii] https://hbr.org/2007/09/the-wisdom-of-expert-crowds

[iv] https://hbr.org/2007/09/the-wisdom-of-expert-crowds

[v] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16586195

[vi] https://www.pwc.com/ee/et/publications/pub/delphi-energy-future.pdf

[vii] http://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/to-improve-cybersecurity-think-like-a-hacker/

[viii] http://www.unido.org/fileadmin/import/16959_DelphiMethod.pdf

[ix] http://forlearn.jrc.ec.europa.eu/guide/2_scoping/meth_delphi.htm#Pros_Cons

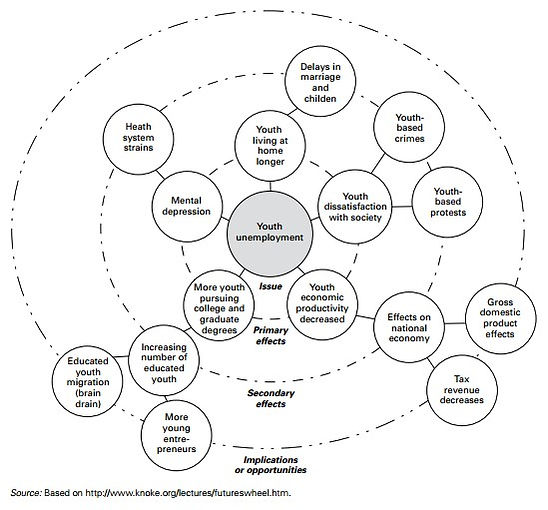

FUTURES WHEEL

Some futures thinking processes are similar to already well-known activities routinely undertaken by groups and organisations. Futures Wheels(FW) resemble mind-mapping reasonably closely, but is more closely aligned to exploring implications and consequences of a specific future issue.

The method was developed in the 1970's, and proponents estimates that a deeply developed wheel can predict 80 percent to 90 percent of the potential implications of the centre under study[i].

WHAT ARE FUTURES WHEELS FOR?

Futures Wheel (FW) – also sometimes referred to as Consequence Wheels or Impact Wheels refer to a structured brainstorming process that can be used to help document, develop and display thinking around future events, trends or issues. This can help in mapping complex relationships and even identifying possible consequences of a given strategic direction or approach, with questions such as:

-

What happens as a result of the central trend?

-

If it happens, what does that mean?

-

What are the consequences of the consequence?

FW help provide second, third and fourth level consequences, which as a level of analysis is often missed by routine analytical methods[ii].

WHAT COMMITMENTS ARE NEEDED?

The level of commitment needed depends somewhat on the reason underpinning the desire to use FW. For example, the method can be used;

-

For individuals (for example, mapping shifting job roles)

-

For small groups (for example, figuring out consequences of broad org. policy or trends at a local level)

-

For larger groups driving strategy or exploring different paths.

The commitments for the first two examples are minor – the process of FW is relatively simple and free software can be accessed in helping to construct the FW.

For a larger construct, a facilitator is often needed to help coordinate the session. Unlike other futures processes that require multiple meetings and rounds of input (such as Delphi), FW can be explored in as little as one session lasting perhaps half a day.

THE PROCESS

-

The first step in producing a Futures Wheel is to place a statement (provocative or otherwise), event or strategic issue in a circle in the centre of a sheet of paper.

-

Step two is to think of and write primary impacts of this statement/event/strategy in separate ovals around the central oval and connect them to the centre with single lines[iii].

-

Next, ‘…take each of these primary effects, one by one, and ask what effects they in turn will have on our lives[iv].’ These secondary impacts of each primary impact should also be noted in their own ovals and connected to the primary impact by a single line each. This then forms the second ring of the wheel.

-

Continue this ripple effect, increasing the number of lines used to join the ovals, until a useful picture of the implications of the event, trend or strategy is clear. This could be three or more lines out, but as in the example below, three lines out is most common.

[i] http://orgs.gustavus.edu/ric/pdfs/Introduction%20to%20the%20Implications%20Wheel.pdf

[ii] http://www.andyhinesight.com/foresight-2/fun-with-futures-wheels/

[iii] http://www.emergentfutures.com/wpdl/Emergent%20Futures%20Consequence%20Wheel%20Tool%20Download.pdf

[iv] http://www.infinitefutures.com/essays/prez/issues/sld020.htm

Figure 8: Example of a Futures Wheel[i]

[i] https://wesharescience.com/na/guidebook/Future%20wheel.pdf

When working on Futures Wheels – depending on the size and enthusiasm of the audience, prompts may be useful. The PESTLE (Political, Economic, Social, Technological, legal, Environmental) shorthand can be around the diagram (i.e. one quadrant for Political issues, one for Economic and so on)

It is also important to complete each ring of the wheel before moving onto the next – following a single primary impact through to secondary, tertiary or consequences can lead to linear thinking that can easily miss consequences – intended or otherwise.

WHAT ARE THE BENEFITS?

FWs have a variety of different applications and hence benefits:

-

Increases the rigour of thinking and helps mitigate linear or one-dimensional thinking.

-

Is inherently network-oriented – and likely to appeal to more modern approaches to work/workers.

-

Can readily identify relationships and unintended consequences.

-

Is intuitive and requires little extensive training for the facilitator.

-

Is highly adaptable to a range of circumstances.

-

Can determine impacts and consequences for a variety of possible strategic directions.

They can also be used in conjunction with, or as a basis for, other futures processes:

-

Output can help feed future scenarios.

-

Output can also guide horizon scanning (and vice versa)

IN PRACTICE

Frequency of FW use in business is difficult to ascertain, much in the same way as brainstorming or mindmapping is. Many utilize it on a daily basis but it often remains hidden from analysis. Academics have utilised FW in many foresight studies, from concerning the future of water in Egypt to the development of the commercial real estate market[i].

WHAT TO AVOID

One of the disadvantages versus other futures and foresights methods is that FW are often viewed only a pre-cursor to other futures methods. Whilst not without merit on their own – in fact they can act as an efficient way of orienting futures thinking – they often lead into other futures methods.

There are some issues to avoid in order to ensure proper use, however:

-

Be aware that some issues may underplay the complexities of contributing factors.

-

Futures Wheels may not clarify whether effects and relationships are correlated or causal.

-

Futures Wheels represent hypotheses, not a guarantee of how the future could unfold.

-

There is no time projection to help gauge urgency.

-

A Futures Wheel shouldn’t be used, alone, to arrive at conclusive decision making.

[i] http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S026483771500407X

CROSS IMPACT ANALYSIS

Multiple sets of forecasts often feature as part of any business leaders strategic planning. Accounting for the interactions between a set of forecasts is where cross impact analysis comes in. In fact, the origin of cross-impact analysis (CIA) should be seen in the context of problems within the Delphi method, which often asked expert participants to offer forecasts on singular events when other items within the Delphi survey could (and would) impact it. Although still used successfully in parallel with Delphi, cross impact models can stand alone as a method of futures research, or can be integrated with other method(s) to form powerful forecasting tools.

WHAT IS CROSS IMPACT ANALYSIS FOR?

Cross-impact analysis refers to a technique – often used in conjunction with scenarios or Delphi that seeks to work systematically through the relations between a set of variables[i]. The biggest danger with any foresight technique is the assumption of linearity and whilst many techniques seek to counter it, CIA does so intrinsically as it seeks to evaluate changes in the ‘…probability of the occurrence of a given set of events consequent on the actual occurrence of one of them[ii].’

There are several specific uses that could see CIA employed;

-

CIA is mainly used in prospective and/or technological forecasting studies.

-

It is commonly used as part of an expert-opinion study (it could be argued that in some cases, CIA is part of the Delphi technique)

-

When exploring a hypothesis and finding points of divergence or agreement within teams or management structures.

WHAT COMMITMENT IS NEEDED?

The depth of the project has a material impact on the time and resources needed to construct it. Accessing a panel of external experts - in the manner of Delphi – could easily mean that up to 6 months is needed, whereas as rough and ready effort needed to provide clarity on an internal issue could be concluded much more quickly. Furthermore, if CIA is used as art of a package of futures techniques, practitioners will need to factor those in as well.

Typically, the method targets participant audiences comprising experts from industry, academia, research and government, which may problematize the issue of convening an expert panel.

The analysis of CIA requires a degree of skill, specifically of modelling knowledge if the practitioner or participants wish to understand how CIA software processes the data. In depth cross-impact analysis methods can be supported by special-purpose software but the basic layout can also be achieved in excel or similar programs.

THE PROCESS

A number of steps are required to complete a CIA process, as outlined briefly below:

Step 1: Issue and expert selection

-

A preliminary list of events related to the issue should be drawn up.

-

Experts, once agreed upon, are normally asked to:

-

Appraise the simple probability of a hypothesis occurring by means of a scale from 1 (very low probability) to 5 (highly probable)

-

Appraise the conditional probability of a hypothesis if the others occur or not.

-

Step 2: Final selection and definition of the events

-

The final list of events should be as clear and as unambiguous as possible.

-

The experts enlisted should have a say on the selected issue. The selection can also be obtained via other futures methods used to collect opinions, such as Delphi.

Step 3: Probability scale and time horizon definition

-

In general, the probability scale for cross-impact methods usually goes from 0 (impossible event) to 1 (almost certain event) with online CIA software.

-

This step also involves determining the time horizon of the forecast, which must be stated explicitly.

Step 4: Estimating probabilities

-

The experts estimate the probability of the occurrence of each event.

-

Conditional probabilities in the matrix are then estimated in response to the following question: ‘If event a) occurs, what is the new probability of event b) occurring?'

-

The entire matrix is completed by asking this question for each combination of occurring event and impacted event.

-

Once completed, results are usually entered on the computer and the program is run (Monte Carlo sampling or similar method)

Extra steps: Generation of scenarios

-

One possible outcome of applying a cross-impact model is a production of scenarios.

-

Sensitivity analysis could also occur, consisting of selecting an initial probability estimate or a conditional probability estimate, about which uncertainty exists.

[i] https://rafaelpopper.wordpress.com/foresight-methods/#Cross-impact

[ii] http://forlearn.jrc.ec.europa.eu/guide/2_design/meth_cross-impact-analysis.htm

Figure 9: An example of an unfilled cross impact matrix[i]

[i] http://discoveryoursolutions.com/images/cross_impact_matrix.jpg

WHAT ARE THE BENEFITS?

The main benefits are:

-

It is relatively easy to implement with regards to skills.

-

Cross-impact methods forces a focus onto links of causality and leads away from linear thinking. Dependency and interdependency are estimated.

-

Is a useful tool for developing knowledge for participants.

-

Can strengthen an array of other futures techniques.

IN PRACTICE

CIA has been in use since at least 1968, when an array of experiments were conducted with the method[i]. Since then a number of examples have proven the worth of CIA.

The Canadian softwood lumber industry has used the method in the face of market issues in the 1990’s. Faced with an ongoing reduction in the quality of its logs, the industry modelled the forecasts of technological innovations. ‘Comparative forecasts were made of the consequences of three technological investment strategies, and comparisons were conducted for six environmental scenarios.’ As a result of the CIA, ‘…a mixed strategy of investment in both processing and product technologies was identified as the best approach for the Canadian softwood lumber industry to maintain profitability and market share in the markets in which it competes with U.S. producers[ii].’

In Germany, CIA was used to help better understand the future(s) of the energy consumption of private households in Germany. It was determined that in order to create scenarios for the household sector, it was necessary to ‘…specify the social, political, economic and technological framework[iii].’ The CIA was used to assess these main drivers and their interactions into account.

WHAT TO AVOID

The method has a number of limitations, such as;

-

The process can prove unwieldy. In fact, with a set of ten events a given expert could be faced with providing around 90 conditional probability judgments, making the task potentially tedious and prone to numbers of participants dropping out[iv].

-

A large matrix could require several iterations and prove time-consuming.

-

Complex systems are difficult to model using only pairs of trends or drivers, since the future is often derived from multiple confluencing trends.

-

As with Delphi and other techniques focussed on experts’ knowledge and judgment, the method’s success depends on the input and competence of the participants.

-

May not be consistent from use to use (given need for expert participants)

[ii] http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.202.7337&rep=rep1&type=pdf

[iv] http://forlearn.jrc.ec.europa.eu/guide/4_methodology/meth_cross-impact-analysis.htm

SWOT

The SWOT (Strengths, Weakness, Opportunity and Threat) method is commonly used by organisations to assess their relative strengths and weaknesses against external drivers which can generate opportunities or threats. Its simple but quite effective if done well. IE: the external forces are adequately identified and the internal strengths and weaknesses wholly honest. This method was created in the 1960's by Albert Humphrey of the Stanford Research Institute, during a study conducted to identify why corporate planning consistently failed. Since its creation, SWOT has become one of the most useful tools for organisations to both start and grow.

WHAT IS SWOT USED FOR?

A SWOT analysis is designed to facilitate a realistic, fact-based, data-driven look at the strengths and weaknesses of an organisation, its initiatives, or government departments goals or even an industry. The organisation needs to keep the analysis accurate by avoiding pre-conceived beliefs or gray areas and instead focusing on real-life contexts. Organisations should use it as a guide and not necessarily as a prescription.

It is used to help you develop your organisations strategy, whether you’re building a startup or guiding an existing organisation. Strengths and weaknesses are internal to your organisation, things that you have some control over and can change. Examples include who is on your team, your patents and intellectual property, and your location. Opportunities and threats are external, things that are going on outside your company, in the larger market. You can take advantage of opportunities and protect against threats, but you can’t change them. Examples include competitors, prices of raw materials, and customer shopping trends, demographics and legislation.

A SWOT analysis organises your top strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats into an organised list and is usually presented in a simple two-by-two grid.

WHAT COMMITMENT IS NEEDED?

The real commitment is one of undertaking a worthwhile Horizon Scan of the things that might impact the organisation within the time frame of the exercise. Equally determining the organisations strengths and weaknesses may involve a number of sources to become truly worthwhile inputs into a SWOT.

THE PROCESS

You can employ a SWOT analysis before you commit to any sort of action, whether you are exploring new initiatives, revamping internal policies, considering opportunities to pivot or altering a plan midway through its execution. Sometimes it's wise to perform a general SWOT analysis just to check on the current landscape of your business so you can improve business operations as needed. The analysis can show you the key areas where your organisation is performing optimally, as well as which operations need adjustment.

Don't make the mistake of thinking about your operations informally, in hopes that they will all come together cohesively. By taking the time to put together a formal SWOT analysis, you can see the whole picture of your business. From there, you can discover ways to improve or eliminate your company's weaknesses and capitalise on its strengths.

While the business owner should certainly be involved in creating a SWOT analysis, it is often helpful to include other team members in the process. Ask for input from a variety of team members and openly discuss any contributions made. The collective knowledge of the team will allow you to adequately analyse your business from all sides.

Characteristics of a SWOT analysis

A SWOT analysis focuses on the four elements of the acronym, allowing companies to identify the forces influencing a strategy, action or initiative. Knowing these positive and negative elements can help companies more effectively communicate what parts of a plan need to be recognised.

When drafting a SWOT analysis, individuals typically create a table split into four columns to list each impacting element side by side for comparison. Strengths and weaknesses won't typically match listed opportunities and threats verbatim, although they should correlate, since they are ultimately tied together.

Billy Bauer, managing director of Royce Leather, noted that pairing external threats with internal weaknesses can highlight the most serious issues a company faces."Once you've identified your risks, you can then decide whether it is most appropriate to eliminate the internal weakness by assigning company resources to fix the problems, or to reduce the external threat by abandoning the threatened area of business and meeting it after strengthening your business,".

Internal factors

Strengths (S) and weaknesses (W) refer to internal factors, which are the resources and experience readily available to you.

These are some commonly considered internal factors:

-

Financial resources (funding, sources of income and investment opportunities)

-

Physical resources (location, facilities and equipment)

-

Human resources (employees, volunteers and target audiences)

-

Access to natural resources, trademarks, patents and copyrights

-

Current processes (employee programs, department hierarchies and software systems)

External factors

External forces influence and affect every company, organisation and individual. Whether these factors are connected directly or indirectly to an opportunity (O) or threat (T), it is important to note and document each one.

External factors are typically things you or your company do not control, such as the following:

-

Market trends (new products, technology advancements and shifts in audience needs)

-

Economic trends (local, national and international financial trends)

-

Funding (donations, legislature and other sources)

-

Demographics

-

Relationships with suppliers and partners

-

Political, environmental and economic regulations

After you create your SWOT framework and fill out your SWOT analysis, you will need to come up with some recommendations and strategies based on the results.

[ii] http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.202.7337&rep=rep1&type=pdf

[iv] http://forlearn.jrc.ec.europa.eu/guide/4_methodology/meth_cross-impact-analysis.htm

NEXT FRAMEWORK

The Next Matrix is a tool that allows an organisation to take both a high level and a detailed analysis of the barriers and enablers of achieving a meaningful vision and implementing the change necessary to achieve it. It highlights how the the characteristics and capabilities of the organisation interact.

The tool includes an element referred to as 'Entrepreneur, Leader, Manager' (ELM) which is an online indicator that identifies the propensity for individuals to want to engage with new ideas and change.

ENTREPRENEUR, LEADER, MANAGER

The Entrepreneur Leader Manager (ELM) indicator is a powerful personal profiling tool which helps individuals to understand how they engage with the process of change and how their perspective may help or hinder them in moving forward into the future. It can also be used to profile individuals in the context of their management team and their peer group to get further understanding of their interactions together.

The ELM indicator is not a psychometric test and it does not tell you about your personality. What it will help you to understand is how your current outlook may affect your perspective in relation to your work, your colleagues and your organisations objectives.

Completing the indicator will generate your personal profile based on the answers you provided in the form of a pie chart. You’ll also have the option to generate your report, which will allow you to download the ELM PDF report, giving insight and analysis relating to your profile.

CEOforesight

It's a challenge staying on top of strategic issues, and no more so than in the case of future changes in the political, economic, social, cultural and technological environment, so we created CEOforesight.

We want to do the heavy lifting for you, by providing a foresight service specifically designed for the CEO.

Simply stated, we do the work, you get the credit.

Contact us so we can discuss how we can able to help you.